ТРИНАДЕСЕТО ИЗДАНИЕ

Международен Симпозиум ИЗКУСТВО-ПРИРОДА Габровци 2024 – Обратно към реката представя произведения на

седем ГОСТУВАЩИ АРТИСТИ

от Корея, Обединеното Кралство, Румъния, Ирландия, Босна и Херцеговина, Белгия и България

СПЕЦИАЛНИ ГОСТИ

от Унгария

И десет от авторите на Артгрупа ДУПИНИ

Специално за участниците програмата на симпозиума включва:

- Артистични авторски презентации

- Специална дегустация с местната бутикова Винарна Ялово

- Културни визити в околията и посещения на забележителности в гр. Трявна и Велико Търново

- Концерт на Котел Джипси Бенд

период:

08 юли – 21 юли 2024

място:

Артцентър Дупини и село Габровци

обл. Велико Търново

Снимки от денят на отворените врати може да намерите тук

Повече за събитиетов текста на Ерос Ищван – художник, изкуствовед, куратор и специален гост на изданието

The Gabrovtsi Naturе Art Symposium

One of the defining tasks of the Western man of the 21st century will be the radical transformation of ideologies and values. Today, the once-ossified right-left bipolar divide has essentially disappeared. The dominant ideologies are no longer determined by their assertion techniques, organised according to their position in the social power structure. The differences of interest between the two once opposing sides are diminishing. We are living in an era of new ideologies based on proposals for solutions to the new challenges of the new millennium: how do we respond to the consequences of globalisation in our daily lives? How close do we let other cultures come to our own? How do we imagine cultures living side by side? How important is it for us to protect the natural environment? What are we willing to give up for it? These are the questions that people today are looking for answers to, and more and more of them feel the need to develop a new vision of the future that is more distant, more alert to the degradation of the natural environment, and more intelligent, rather than the idea of perpetual expansion. Artists, many of whom, breaking with the concept of the creative industry, are increasingly looking to the total life as the arena for their work, are naturally also called upon to play a role in this search. The rise of public art, street art and environmental art is a good illustration of this attitude on the part of artists who are already leaving the gallery system.

The efforts of artists working in the natural environment also resonate with this general desire for social improvement, but they are content to make ‘small gestures’, leaving the aggressive reorganisation of the world to the engineers in urban centres, far from the organised playing field of cultural policy. Although only some people examine this art form from this perspective, the growing ecological problems mean that nature art is as relevant and socially engaged a form of artistic expression as the activist art forms that are flourishing today in response to social phenomena.

How has art been returned to nature? What is nature art? How did this exciting, comprehensive field of visual art emerge?

With the advent of the Renaissance and then the Enlightenment, the sacred, ceremonial functions of works of art gradually faded and their aesthetic and economic values came to the fore. The emblematic institutions of collective memory, museums and their collections, which were intended to present and preserve for posterity the memories and historical merits of the ruling classes, are now emerging. By the 20th century, art had become ‘trapped’ in the buildings, museums, galleries, theatres, and concert halls – the force fields of a well-organised system of cultural institutions. In modern museums and galleries, works of art are displayed in sterile spaces, alienated from their environment. In these ‘white boxes’, the work is not architecturally part of the surrounding environment, so there is minimal interaction between them, based essentially on primary visuals.

The Impressionists, with their devotion to nature, were among the first to emphasize the relationship between art and its natural environment. This unique bond was further explored by artists like Constantin Brancusi, who placed his essential works in a natural park he designed a small Romanian town with a rural atmosphere, in contrast to the practice of the time of installing public sculptures (Table of Silence, Column of Infinity, Gate of the Kiss). This practice, which began in the 1960s, has since become a fully accepted and celebrated part of the art world.

However, the natural, programmatic, physical encounter between art and nature occurred in the 1960s in the context of the land art movement in America and the arte povera movement in Europe. After that, placing artworks in a natural context became a fully accepted practice. The proliferation of this practice has led to the creation of a succession of art centres that hold their symposia and events on the outskirts of towns and cities, in the parks of small villages, castles, on the coast, or in abandoned coal mines.

By the 1990s, the practice of artistic interaction with nature had become embedded in contemporary art. Today, a growing number of artists seek to recreate harmony with nature, directly using natural materials, objects, energies, and sites in their work. Making direct physical contact with nature is the essence of the creative process.

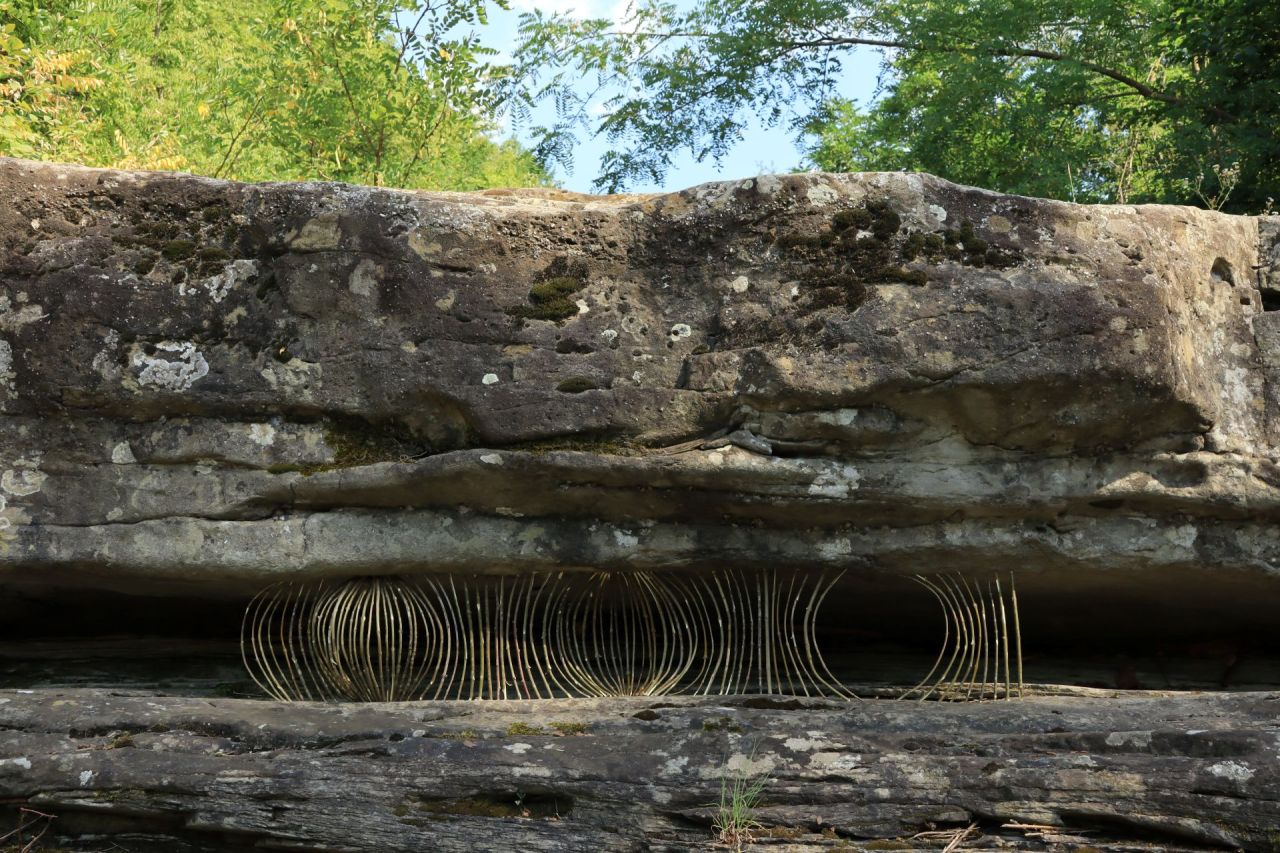

These artists create works far from the urban environment, usually in a natural or even rural setting, mainly using craft techniques and rarely using mechanical means. The ‘sign’ thus created reinforces the specificity and uniqueness of the landscape. Their interconnectedness is immutable, and the works cannot exist outside this specific environmental context. In making the work, the artist often uses natural materials found in the environment, which are usually ephemeral and degradable.

In the case of nature art, however, not only the artistic site but also the interaction with the villagers, the „real artists of nature,“ are of particular importance. Artists often work with the local community, and craftsmen and artisans are often actively involved in the creative process.

The resulting ephemeral works, which exist in a time of cyclical changes in nature, overturn the conventional myth of the work of art as eternal but also contradict the institutional and collecting logic entirely: it is impossible to clarify their ownership, and in most cases the works, enforcing their laws, return to nature, with the artist or the rights holder retaining at most the copyright and the remaining documentation.

We have, therefore, witnessed the birth of a new movement in the last 2-3 decades. In this seemingly isolated rural environment, several internationally renowned natural art events have been created, proving that the relationship between the centre and the periphery is no longer firmly established and can even add to the works being created here. Natural art as a term has now become part of the vocabulary of contemporary art, and its emergence as a subject in some European higher education institutions is evidence of a process of canonisation of the movement, a trend that is likely to increase in the years to come.

Since the turn of the millennium, a number of art centres and art colonies have been established around the world where nature is the focus of creative activity. Examples include GNAB in Korea, Sandarbh in India, Arte Sella in Italy, Noszvaj Cave Dwellings in Hungary, Gyergyószárhegyi Artists’ Colony and Ethigo Tshumari in Japan, to name a few of the most important ones. These organisations are connected to each other as a loose network, mainly for information flow. Co-operation rather than competition is their organisation’s motto, but they also share the common characteristic of avoiding participation in a centralised structure or cultural policy strategy.

The Duppini Art Group, located in the dead-end village of Gabrovti, near the old Bulgarian capital, Veliko Tarnovo, has been holding its annual summer symposium there for 24 years.

The group was founded in 1999 and began its activities in a completely abandoned village, buying up derelict, ruined properties and renovating them to make them suitable for art.

Here, they created the natural setting that has become their trademark over the last two decades and has made them internationally known.

The opportunity to move on came when they were given the use of a closed reformatory school’s building in a neighbouring village, also in decline, to set up their creative centre. The building itself bears the architectural and technical traces of the past regime, which can be refreshingly interesting, especially for artists from the West or the Far East, a nostalgic time travel for Eastern Europeans, an exotic experience for young people. The only pub in the village is guaranteed to leave a deep impression on all who enter, its decorative elements reflecting the owner’s strong ideological stance, proudly displaying paintings of Lenin, Stalin and Todor Zhivkov, photographs and relics of a not-so-memorable time.

The village itself is an architectural way of exploring the layers of time of past centuries, offering valuable insights into times gone by, which often have an impact on an artist from another culture.

Various grants finance the two-week event, which is characterised by the community’s voluntary work (meals prepared by the members, excellent ingredients, excellent rakia cooked by the members and their relatives). In other words, the pleasure of being together, eating together, doing together, with a minimum of financial support.

Only 20 people live in the village, which is situated along a beautiful riverbed. They are involuntarily part of the event as the creation process takes place throughout the village. The unique rural space and beautiful, unspoilt nature provide the contextual background for the works.

The materials used are also typically taken from natural materials found in the area, and sponsored materials such as those donated by the forestry company.

The artists who come here are transported to another dimension of time, forced to leave the flow of everyday life behind and concentrate only on creating and getting to know each other’s art more deeply. The evening presentations, helping each other to develop their work, make the relationships formed here more qualitative, more lasting and, from experience, more enduring. During the time spent here, important questions about our everyday lives will emerge as a matter of course, it will almost become inevitable to explore the bigger picture of life. We can be part of a kind of meditative dissolution.

Here, it begins to emerge that the advance of the information society has fundamentally changed our daily lives and the quality of our human relationships. Observing our daily lives and experiences here makes us understand that the spread of information and communication technology is increasingly isolating the individual and weakening small communities’ norm-broker and controlling role. We realise that for people who rarely come into contact with art, the experience of participating in the creation of a work of art, the task of creating the conditions, and the dedicated participation in a common cause can be a means of slowing down and hindering this process of alienation. In addition, the work that results from such collaboration also results in the participants, the villagers, feeling a sense of ownership of the works of art bearing the hallmarks of contemporary forms, significantly widening the channels of reception, not to mention the ‘side’ effect that the resulting works of art also enrich the community, even if only temporarily. These aspects, which are most likely to be valued in the future, were recognised by the group, currently led by Rumen Dimitrov Popa, when they set out to organise the artists’ colony.

With a background in education (two of them also teach in a high school with a long tradition), another outstanding merit of the organisers is their emphasis on involving university students and younger generations in the day-to-day work of the symposium. They are convinced that joint creative work can help to articulate ecological concerns in a multifaceted artistic way with an underlying content and that students will be more likely to communicate effectively in their environment the concern about the degradation and loss of value of nature and to raise awareness about the importance of preserving cultural heritage. In addition, through their creative work, art students will become part of the artistic-social discourse, not only in theory but also in practice, on the reassessment of the artist’s position in society, their responsibility and the importance of their active participation in public affairs.

I am convinced that the work that has been going on for 24 years now, organised by the Duppini Art Group in this beautiful cul-de-sac village, often more effective than the dry propaganda spread by the media can act as a model method for keeping small rural and urban communities together. Last but not least, it provides an opportunity to rethink the sites of contemporary art, as this magical rural setting adds a layer of content to the works produced here. The members of the Duppini Art Group may be unaware of how important a mission they are part of.

ГОСТ-АРТИСТИ

Yeji Oh / KR

Ivan Smith / UK

Emil Cristian Ghita / RO

Nell Lenoir / BE

Jessica Daly / IRL

Dino Tozo / BIH

Anatoli Vanchev / BG

СПЕЦИАЛНИ ГОСТИ

Eros Istvan / HU

ФОТОГРАФИ

Славчо Славов

Илияна Григорова

АСИСТЕНТ-ДОБРОВОЛЦИ

Никола Михов

Екатерина-Мария Миткос

АРТГРУПА ДУПИНИ

Румен Димитров-Попа

Орфей Миндов

Румен Рачков – Дървесния

Славчо Славов

Катерина Милушева

Cristan Seușan / RO

Кирил Георгиев

Калин Михов

Лидия Къркеланова

Александра Ангелова

Марина Ангелова

Найден Колев

Богомил Иванов / Илияна Григорова

Артгрупа Дупини изказва специални благодарности на: Христо Медникаров, Величко Величков – Вичо, Милена Градинарова, Пенчо Трифонов, Димитър Димов, Гюнай Мустафов, Диан Иванов, Емил Бачийски, Калин Йорданов, ВеликоТърново и всички приятели подкрепящи Артгрупа Дупини.

Симпозиум ИЗКУСТВО-ПРИРОДА Габровци 2023 се осъществява с финансовата подкрепа на Община Велико Търново и благодарение на часни дарения. Симпозиумът е реализиран в партньорство с Кметство Габровци, НГПИ „Тревненска школа“, гр. Трявна, Школа „Дедал“, гр. Варна, Винарна „Ялово“, с. Ялово, Пивоварна „Бритос“, Държавно Горско Стопанство – Болярка, METRO, Велико Търново.

Организатор на събитието е Артгрупа Дупини, място на събитието – Duppini Art Center & Residency.